By Heiner Fruehauf

According to the principal investigator’s expanded version of the Han dynasty cosmograph, ancient Chinese scientists associated the Heart network with the 5th lunar month of the year. The Erya encyclopedia (fl. 3rd century B.C.E) contains an enigmatic list of ancient designations for the twelve months, which the Japanese sinologist Hayashi Minao believed to be the names of twelve month gods.[i] In this book, the name of the 5th month is listed as Gao 皋. This character has a variety of complex meanings, which upon careful examination reveal an intricate web of relationships that tell a rich and coherent story all in itself. This story greatly illuminates the functional role of the heart network, which is presented only in rudimentary fashion in the medical classics.

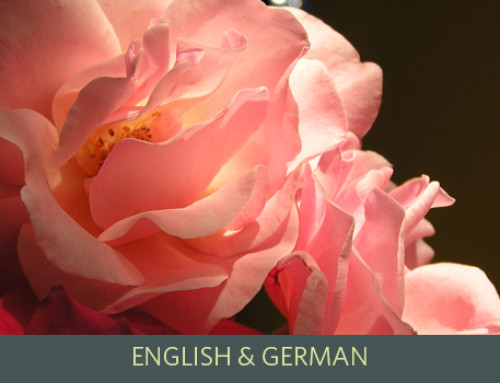

Painting by Wang Hui, The Landscape of Mt. Song (17th century), The Cleveland Museum of Art.

The primary meaning of Gao is “high and lofty,” and Han chroniclers used it almost exclusively to designate places or persona of imperial rank. Several sources relate it directly to Mt. Song, the central one among the five sacred mountains of Daoist geography, which features prominently in both the mythology and archeological record of ancient China. Mt. Song is a cluster of mountains in the vicinity of the well-known Shaolin Monastery in today’s Henan Province, primarily comprised of Mt. Chonggao (“High and Lofty”) at the center, and Mt. Shaoshi and Mt. Taishi to either side. More specifically, Gao can be interpreted as the name of a pair of three-headed protector spirits of this mountain range, where sacrifices in honor of the mountain deities have been performed since prehistoric times.[ii] According to the Shuowen jiezi dictionary (100 C.E.), furthermore, gao means “to ritually invoke (the spirits of the gods and/or ancestors)”—in essence, to pray (a related homonym is gao 告, “to communicate with,” or “to ask for grace from a higher source”).[iii] This interpretation is confirmed by the fact that Mt. Song is one of China’s oldest natural “altars,” where archeological finds have recently confirmed that sacrifices were performed here as early as 5,000 years ago. For the ancient Chinese, therefore, this was the quintessential place where humanity ritually ascended to connect with the realms of spirit. As the Jiaoshi yilin (2nd century B.C.E.) states: “In the region of the City of the Sun and Mount Taishi, this is where the Manifest Spirit [shenming] resides.”[iv]

This theme of prayer, sacrifice, and connection to the spirit world is continued in the symbolism of the first three “cyclically appearing phenomena of the natural world” (wuhou) associated with the 5th month in the Liji and other early texts, namely “the praying mantis is born, the shrike begins to cry, and the bull-headed shrike ceases to sing.”[v] The body posture of mantis religiosa, or tanglang 螳螂 (“Officer of the Sacrificial Hall”) in Chinese, make it an obvious candidate for symbolizing the human characteristic of honoring creation through ritual gratitude. All three animals, moreover, are notorious creatures of prey, involved in the business of constant “sacrifice.” All three of them, furthermore, are sources of recognized medicinal substances in the Chinese materia medica (mantis cocoon, mantis body, shrike feathers, bull-headed shrike meat). Fittingly, they were categorized as substances said to exert a calming influence on the heart network.[vi]

Some time during the late Zhou and early Han dynasties, the early ceremony of worshipping the nature spirits became personified in the cult of Houtu 后土 (Earth Deity, Mother Nature). In China’s most distant past, most inhabitants of the central plains belonged to matrilinear tribes, and sacrifices to the Earth spirits appear to precede the worship of Heaven. The Earth Deity, alternately called Dizhi (Respected Earth Spirit), was thought to reside in the center of the ancient world (Mt. Song). During Zhou times, the central “nature altar” of Mt. Song was replicated in the institution of the ancestral temple and the various rituals of the dynastic state cult. While the Heavenly Spirit, addressed as Imperial Lord Supreme One, was pictured to reside in the highest level of the temple compound, the so-called Mingtang (Hall of Brightness), the central portion of the temple was occupied by Houtu Gong (Palace of the Earth Deity). It was here that the age-old rituals involving Mother Nature continued in institutionalized form. It was by design that these rituals were executed during the central temporal peak of the year, the time of the summer solstice that occurred in the middle of the 5th lunar month. This correlation is further corroborated by the tidal hexagram 44 (Gou 姤), which was often used to represent the energetic momentum of the 5th month during Han times. Gou is usually translated as connection, unity, or intercourse, but a rendering of the single components of this character simply yields the meaning: “The Queen.”

Houtu was regarded as the mother deity of nature, and an expression of its radiant life force and beauty–all compassionate, ever present. Mt. Song, therefore, was clearly regarded by the ancient Chinese as the place where spirit incarnates as shenming (the mystery of spirit revealed in manifest form). In the foundational classic of Chinese medicine, the most pertinent quote on the nature of the organ networks utilizes this term to define the function of the heart: “The heart occupies the office of lord and ruler; the function of the manifesting spirit [shenming] issues from it.”[vii] In this famous passage, shenming is generally translated as “brightness of spirit” by modern commentators, giving rise to the contemporary TCM notion that the heart governs all mental faculties. However, the term shenming features prominently in Han dynasty texts, and can be defined in a much more precise and expansive fashion.[viii]

In the process of consulting this symbolic background, therefore, a much deeper function of the heart becomes revealed. The authors of the medical classic consciously made reference to the heart as a microcosmic reflection of Mt. Song—viewed as the most central and lofty place on earth, which in turn was associated with the central region in the sky belonging to the Supreme Ruler–its nature spirits, and the Earth Deity. It is a prime example for the defining characteristic of ancient Chinese symbolism, wherein the layers of the heavenly, earthly, and human spheres, as well as the spatial and temporal dimensions on the cosmograph signify each other, point toward each other, and represent each other.

The single term Gao is thus capable of transmitting the following array of functions attributed to the healthy “Heart”–all recognized by scholar-practitioners of Chinese medicine as valid criteria for assessing the physiology and pathology of the heart network:

- The quality of nobility and leadership

- The virtues of selflessness, surrender, and sacrifice

- The quality of connection, especially in relation to nature and the realm of spirit

- The creation of unity and sacred space

- The quality of embodiment and manifestation

- The promotion and perception of beauty

- The quality of “making love from the perspective of a woman”[ix]

- The ability to achieve ecstasy and orgasm[x]

Endnotes

[i] See Hayashi Minao, “The Twelve Gods of the Chan-Kuo Silk Manuscript Excavated at Ch’ang-sha,” in Noel Barnard, ed., Early Chinese Art and Its Possible Influence in the Pacific Basin, 2 vols., vol. 1, p. 123-187.

[ii] The Chu Silk Manuscript cited by Hayashi Minao contains an illustration of the deity Gao, featuring the image of a three-headed creature; see ibid., p. 96. In the classic of mythological geography, Shan hai jing, moreover, a pair of three-headed mountain spirits are described which are directly associated with Mt. Shaoshi and Mt. Taishi, the two neighboring peaks of Mt. Chonggao: “Mount Younghouse [Shaoshi] and Mount Greathouse [Taishi] of the Bitter mountain range are both sacrificial mounds. … In their appearance, their deities both have a human face and they have three heads;” see Anne Birrell, tr., The Classic of Mountains and Seas, Harmondsworth (Penguin, 1999), p. 84.

[iii] From Shen Xu’s Shuowen jiezi; see Kejing, Tang, ed., Shuowen jiezi jinshi (A Contemporary Commentary of ‘Explicating Simple and Analyzing Complex Characters’), 2 vols., Changsha (Qiuli Shushe, 2002), vol. 2, p. 1425.

[iv] Yanshou Jiao, Yilin (‘Yijing’ Transmutations), in Daozang, vol. 36, p. 183.

[v] See Yingda Kong, ed., Liji zhengyi (Authentic Meaning of the Classic of Rites), in Yuan Yuan, ed, Shisan jing zhushu (The Thirteen Classics with Annotations and Commentary), 2 vols., Beijing (Zhonghua Shuju, 1982), Volume 1, p. 1275.

[vi] See Li Shizhen’s 16th century Bencao gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica), in Digital Heritage Publishing, Siku quanshu (Complete Library of the Four Treasuries), Shanghai and Hong Kong (Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe), no page numbers.

[vii] From chapter 8 of the Huangdi neijing suwen. See Nanjing Zhongyi Xueyuan, ed., Huangdi neijing suwen yishi(The ‘Simple Questions’ Portion of the ‘Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine’, with Translation and Commentary), Shanghai (Shanghai Kexue Jishu Chubanshe, 1991), p. 69-70.

[viii] See, most notably, the definition of shenming in the Huangdi neijing itself, “Yin and yang … [are nothing but] a temporary vessel for the process of spirit manifestation (shenming);” in Huangdi neijing suwen yishi, p. 453.

[ix] The Yijing expert Frank Fiedeler’s interpretation of hexagram 44; see Frank Fiedeler, Yijing, München (Diederichs, 1996), p. 396.

[x] The summer solstice is called xiazhi 夏至, “summer climax”; orgasm is often described as a “fighting and eventual division of yin and yang” in Chinese medicine–similar to the energetic momentum of the 5th month, which marks the dividing line between the expanding and contracting parts of the year.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.