Translations

It is one of the goals of this website to participate in the global movement of preserving and appreciating ancient wisdom, for the specific purpose of utilizing its variegated modes of diagnostic and therapeutic knowledge in a modern clinical context.

It is one of the goals of this website to participate in the global movement of preserving and appreciating ancient wisdom, for the specific purpose of utilizing its variegated modes of diagnostic and therapeutic knowledge in a modern clinical context.

The field of Classical Chinese Medicine encompasses a vast reservoir of extant materials, comprising a cache of thousands of documents written between 500 B.C.E. and the 1930s. The knowledge therein stems from the direct observation of natural processes, cultivated through a millennia long tradition of textual commentaries. The ancient Chinese first recorded macrocosmic cycles and patterns in the form of graphic symbols; followed by the creation of pictograms that gave names to the processes of nature; followed by the composition of text that gave details to the names; followed by the formation of commentaries on the textual record.

Much of this rich depository of scientific thought on the interconnection between macrocosm and microcosm remains available in classical Chinese. Yet even in China itself, the number of people who are able to read and understand these records at a deep level is dwindling. For Western readers, only a small fraction has been translated into English or other European languages. In both East and West, moreover, the interest in classical texts appears to be waning, perpetuated by the belief that ancient documents may have some historical value, but that modern textbook interpretations of the principles of Chinese medicine have far greater clinical relevance. In contrast to this development, most ancient master physicians report that they reached their level of clinical achievement by seeking “proximity to the source” through the life-long immersion in the original wellsprings of Chinese cosmology, philosophy, and medicine.

While it may be impossible to create a complete record even in the original Chinese, this section of the site is designed to participate in the evolving process of translating classical Chinese medicine source materials of the broadest possible variety and flavor. We hope that practitioners, students, and recipients of Chinese medicine will thus gain an additional opportunity to experience the original beauty and sophistication of this medicine.

The Liver and Gallbladder: Selected Readings

BY VARIOUS AUTHORS

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

The nature of wood is to spread. Once food qi enters the stomach, it relies entirely on the spreading and dredging function of liver wood, and it is only because of this influence that the food is transformed. If the liver's pure Yang does not rise, it cannot spread and dredge the grain and fluids, and distention and discomfort in the middle region will be the inevitable result. The liver is associated with wood.

A Description of the Therapeutic Uses of Aconite by the Ming Dynasty Scholar-Physician Zhang Jingyue (1583-1640)

BY ZHANG JINGYUE (1583-1640)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

GERMAN TRANSLATION BY MARKUS GOEKE

The flavor of Fuzi is pungent and sweet, and becomes extremely salty if immersed in brine. Its qi is very hot. This herb, therefore, carries within the energy of yang within yang. It is described as toxic. Its (toxic) effect is controlled by Renshen (ginseng), Huangqi (astragalus), Gancao (licorice), Heidou (black beans), Lüxijiao (green rhinozerus horn), Tongbian (human urine), Wujiu (Herba Stenolomae), and Fangfeng (siler).

Zhang Zhicong (fl. 1619-1674): On Fuzi

BY ZHANG ZHICONG (1610-1674)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

GERMAN TRANSLATION BY MARKUS GOEKE

The flavor of Fuzi is pungent, its qi is warm, and it is extremely toxic. It treats wind cold pathogens that induce coughing and other counterflow issues, wind damp arthritis causing wandering pain and constriction, and knee pain with inability to walk. It breaks up tumors and masses, and heals blood accumulations as well as wounds caused by metal objects. The best Fuzi is produced in Mianzhou in the region of Shu.

Yang Tianhui: Notes from My Visit to the Fuzi Growing Area of Zhangming County

BY YANG TIANHUI (Song Dynasty, 1039 CE)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

The following text represents the most detailed pre-modern description of the traditional cultivation of medicinal aconite in China. It was written more than 900 years ago by a Sichuanese official in charge of Zhangming County. Zhangming is situated in the location of today’s Jiangyou County, epicenter of the recent Sichuan earthquake, which has been identified by all ancient materia medica experts as the only place where genuine Chinese aconite should be sourced from.

GERMAN TRANSLATION BY MARKUS GOEKE

On Humanity’s Emotions and Higher Virtues: A Passage from the Chapter “Qingxing” in the ‘Baihu tongde lun’ (Discussions on the Power of Virtue in the White Tiger Hall; attributed to Ban Gu) fl. 1st Century CE

BY BAN GU (fl. 1st Century CE)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

情性者,何謂也?性者,陽之施;情者,陰之化也。人稟陰陽氣而生,故內懷五性六情。情者,靜也,性者,生也,此人所稟六氣以生者也。故《鉤命決》曰:「情生於陰,欲以時念也;性生於陽,以就理也。陽氣者仁,陰氣者貪,故情有利欲,性有仁也。」

What is the nature of our emotional disposition (qingxing)? Our moral values (xing) represent an expression of yang, while our emotional urges (qing) are a transformation of yin...

Fuxing Jue and Tangye Jing Translation Project: Preface

TRANSLATED BY MICHAEL DELL'ORFANO

EDITED AND CRITICALLY ANNOTATED

BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

The Hermit says: Every student of the Dao and all seekers of longevity must first learn how to expel disease. Practitioners often suffer from chronic health problems or acute manifestations of seasonal illnesses. In this case, one needs to first employ the systematic methods of tonifying or reducing the five zang organs by imbibing several doses of herbal medicine.

Introducing the Fuxing jue (Extraneous Secrets) and Tangye jing (Decoction Classic) Translation Project

BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Chinese herbal formulas are typically distinguished as jingfang (classical remedies) or shifang (contemporary remedies). During the last millennium, the origin of all classical formulas has generally been attributed to the Shanghan zabing lan (Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and Miscellaneous Diseases), Chinese medicine’s seminal work on the systematic categorization of disease patterns and corresponding formulas by the Han dynasty scholar-physician Zhang Zhongjing (150-219 ACE). Historical sources reveal, however, that at least eleven classical herb primers (jingfang) existed before Zhang’s birth.

Li Jie: The Life Story of a Forgotten 20th Century Master of Nourishing Life

BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

ADAPTED AND TRANSLATED FROM BIOGRAPHICAL TEXTS BY GUI SHOUZHEN, WANG QINGYU, AND WANG CHUNWU

The Hermit With the Ubiquitous Smile (Huanxi Daoren), Master Li Jie, also carried the epithets Taiqing (Supreme Purity) and Yonghong (Eternally Magnificent). He was born in Mingjing Village of Jiangyou County in Sichuan Province during the 2nd year of the Qing dynasty emperor Guangxu’s reign (1876). There, he is remembered as a child of extraordinary intelligence with an interest in martial arts, especially stick and sword forms. At age 7 he entered into private education, and eventually passed the test to become a mandarin of the first degree (Xiucai) at age 25. He was the first person ever in Mingjing Village who achieved this official rank, and with it came the love and adoration of his community. Afterwards, he worked as a teacher in local private schools around the counties of Jiangyou and Jiange.

An Excerpt from Qianjin yifang (Supplemental Prescriptions Worth a Thousand in Gold) on the Importance of the Acupuncture Point Names

BY SUN SIMIAO (581-682)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

None of the acupuncture names were chosen randomly, all of them contain deep meaning. All point names containing the character for the wood element 木 are related to the Liver. All point names associated with Spirit (shen) 神 are related to the Heart. All point names associated with metal 金 or jade 玉 are related to the Lung. All point names associated with water 水 are related to the Kidney. Similarly, the Spirit’s state of movement is also potentially reflected in the point names. All points with the character Fu 府 (Storage) in their name affect the gathering of Spirit.

Guizhi (Cinnamon) – From Bencao qiuzhen (Exploring the True Meaning of the Materia Medica, 1769)

BY HUANG GONGXIU (18th Century)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Cinnamon twig primarily enters the muscle layer at the surface of the body. At the same time, it enters the heart and liver channels. It is the branch of the cassia tree which also yields cinnamon bark. Cinnamon twig is light, its nourishing essence is pungent, and its color is red (therefore its affinity to the heart). The action of cinnamon twig is rising without descending.

FROM BENCAO QIUZHEN (EXPLORING THE TRUE MEANING OF THE MATERIA MEDICA, 1769)

The Qualities of a Good Physician

BY ANONYMOUS (12 Century)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Everyone who walks the path of healing has to first understand the fundamental principles that are behind all technical aspects of medicine. Only then should herbs and other modalities be prescribed. If healing is approached from the underlying source, all treatment efforts will be sublime and clinical results will naturally follow.

Wuzhuyu – Evodia (Translation)

BY HUANG GONGXIU (18th Century)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Wuzhuyu (Evodia ruticarpa) eliminates counterflow of cold liver qi. Its flavor is bitter, and its quality is hot and dry. It is slightly toxic. It has a primary affinity to the qi layer of the jueyin networks. It counteracts bloating. Li Dongyuan once said: “For a situation where turbid yin toxins do not descend and cause severe counterflow symptoms above, in severe cases accompanied by bloating and swelling, Wuzhuyu is the only substance that can effectively treat this condition.” Overuse of this herb, however, will cause harm to a person’s source qi.

FROM BENCAO QIUZHEN (EXPLORING THE TRUE MEANING OF THE MATERIA MEDICA, 1769)

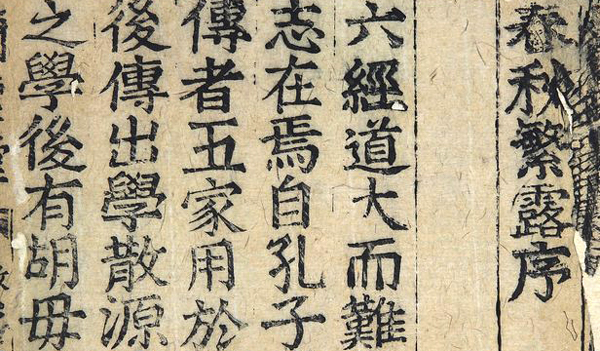

The Path of Acting in Accordance with Heaven (From Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals) – A Monograph on Longevity

BY DONG ZHONGSHU (179 - 104 BCE)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Dong Zhongshu was a Han dynasty scholar with Confucian inclinations. His most important work, potentially a collaboration of different authors, is the Chunqiu fanlu (Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals). Written around the same time that the main classic of Chinese medicine (Huangdi neijing) was first edited into a coherent whole, it contains a variety of treatises on yin-yang cosmology and the five phase elements. In particular, it establishes the central importance of the earth element in Chinese philosophy, a concept that later took on pivotal importance in the development of Chinese medicine theory.

Guizhi – Cinnamon Twig (Translations)

BY HUANG GONGXIU, ZHANG XICHUN

(18th and 19th Centuries)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Cinnamon twig primarily enters the muscle layer at the surface of the body. At the same time, it enters the heart and liver channels. It is the branch of the cassia tree which also yields cinnamon bark. Cinnamon twig is light, its nourishing essence is pungent, and its color is red (therefore its affinity to the heart). The action of cinnamon twig is rising without descending. Therefore, it can also enter the lung and facilitate uninhibited movement of qi, and enter the bladder channel and stimulate water metabolism.

INDIVIDUAL MONOGRAPHS

Fuzi – Aconite (Translations)

BY HUANG GONGXIU, ZHANG XICHUN

(18th and 19th Centuries)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Aconite primarily enters the vital gate of life (mingmen). Its nutritive essence is pungent and extremely hot. Aconite is purely yang in nature and thus toxic. Its function is to move being confined to one place, so it is known to move through all twelve channels, and there is no place in the body it can not reach.

INDIVIDUAL MONOGRAPHS

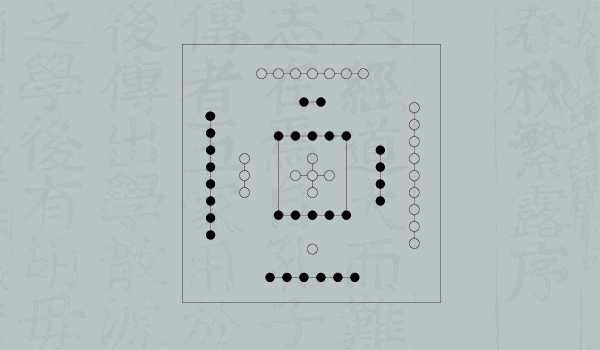

Liu Yiming: Die Flusskarte

BY LIU YIMING (18th century)

GERMAN TRANSLATION BY BENJAMIN WITT

Liu is the most influential Daoist writer and commentator in the last 500 years. He is known for translating some of the esoteric and highly symbolic concepts of Daoism into clear language. His commentary on the River Map is a vital piece for the understanding of yin/yang and Five Phase Element theory.

All Disease Comes From the Heart (translation)

BY HUR JUN (XU JUN) (16th Century)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

The sage healers of ancient times were able to heal the heart of humanity, and thus prevent disease from arising. Today’s doctors only know how to treat disease when it has already manifested in physical form, and don’t know anymore how to work with the heart.

How a Great Physician Should Train for the Practice of Medicine

BY SUN SIMIAO (581-682)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Everyone who aspires to be a great physician must be intimately familiar with the following classics: the Simple Questions (Huangdi neijing suwen), the Systematic Classic of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (Zhenjiu jiayi jing), the Yellow Emperor’s Needle Classic (Huangdi neijing lingshu), and the Laws of Energy Circulation from the Hall of Enlightenment (Mingtang liuzhu). Furthermore, one must master the twelve channel systems, the three locations and nine positions of pulse diagnosis, the system of the five zang and the six fu organs, the concept of surface and interior, the acumoxa points, as well as the materia medica in the form of single herbs, herb pairs, and the classic formulas presented in the writings of Zhang Zhongjing (fl.150-219, author of the Shanghan zabing lun)...

Promoting Health and Relaxation During the Four Seasons

BY GAO LIAN (16th Century)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

The following is a presentation of four famous seasonal tableaux by Gao Lian, a 16th century poet and medical scholar who was an ardent proponent of the art of nourishing life. They originally appeared in Gao's book, Zunsheng bajian (Eight Pieces on Observing the Fundamental Principles of Life), which Chinese physicians used to regard as a comprehensive source of lifestyle related information. Recommencing one of the main themes of the Neijing, these seasonal portraits can be read as a typical attempt to translate the densely crafted teachings of the classic into more contemporary language.

Five Phase Element Relationships

BY WAN MINYING (14th Century)

TRANSLATED BY HEINER FRUEHAUF

Metal is generated by Earth; if there is too much earth, Metal will be buried. Earth is generated by Fire; if there is too much Fire, Earth will be charred. Fire is generated by Wood; if there is too much Wood, Fire will flare. Wood is generated by Water; if there is too much Water, Wood will be washed away. Water is generated by Metal; if there is too much Metal, Water will be grimy.