Adapted and Translated from Biographical Texts by Gui Shouzhen, Wang Qingyu and Wang Chunwu

By Heiner Fruehauf

National University of Natural Medicine, College of Classical Chinese Medicine

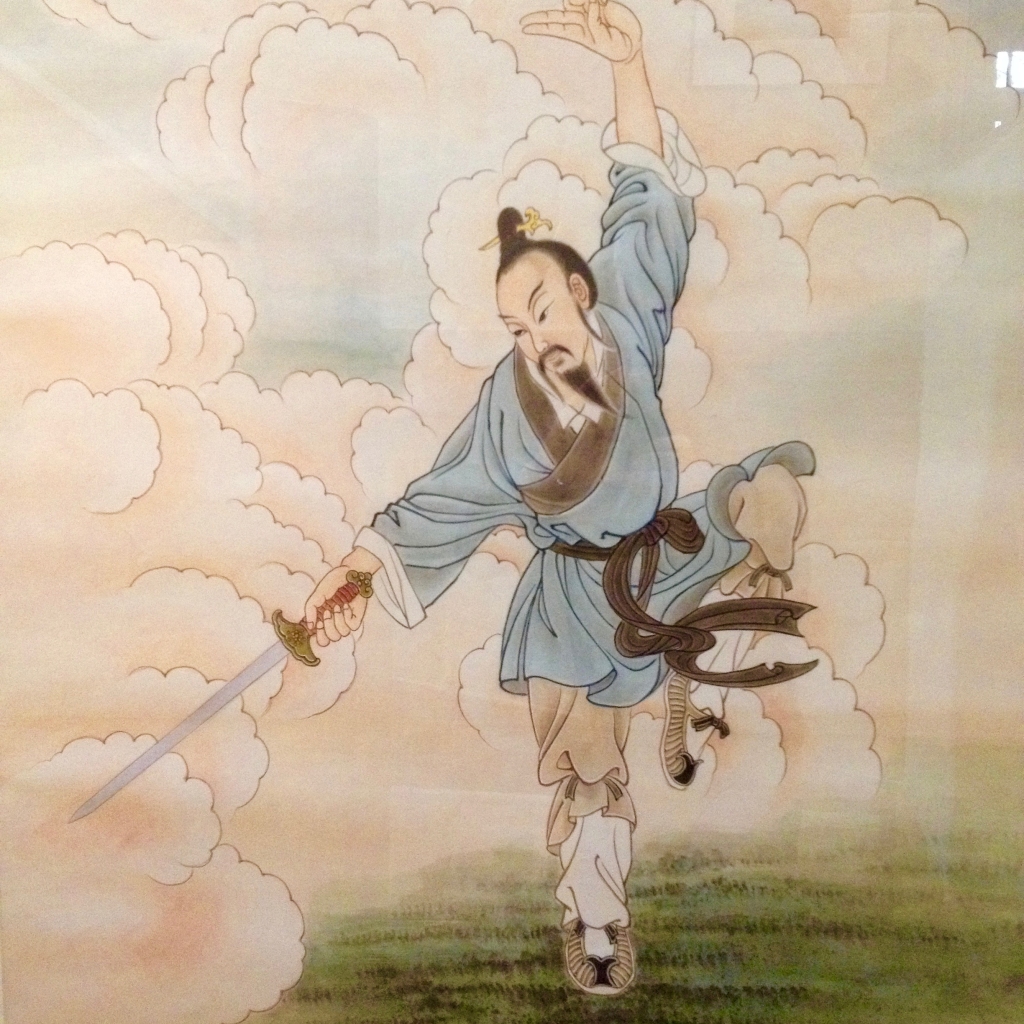

Painting of Li Jie by Xie Linfeng

The Hermit With the Ubiquitous Smile (Huanxi Daoren), Master Li Jie, also carried the epithets Taiqing (Supreme Purity) and Yonghong (Eternally Magnificent). He was born in Mingjing Village of Jiangyou County in Sichuan Province during the 2nd year of the Qing dynasty emperor Guangxu’s reign (1876). There, he is remembered as a child of extraordinary intelligence with an interest in martial arts, especially stick and sword forms. At age 7 he entered into private education, and eventually passed the test to become a mandarin of the first degree (Xiucai) at age 25. He was the first person ever in Mingjing Village who achieved this official rank, and with it came the love and adoration of his community. Afterwards, he worked as a teacher in local private schools around the counties of Jiangyou and Jiange.

Later, he became a Daoist monk. Here is the story of how this unusual development came about. It has been only in recent years that a new and revised “History of Jiange County” has been produced, and the participating researchers provided the following information. It all started during the reign of the Guangxu emperor (1875-1908), when the government of the Qing had become corrupt, officials routinely struck deals that betrayed the interests of the country, so that chaos ensued and everyday life for the common people became highly disturbed. Similar to other areas around the country, the Boxer Rebellion swept through Northern Sichuan and many peasants in Mingjing Village took up crude arms to execute corrupt officials and representatives of foreign imperial powers. In this environment, Li Jie became a staunch opponent of the corrupt Qing government that was now headed by Empress Dowager Ci Xi. Students from that time later still remember his passionate lectures on the pitfalls of Chinese history and the dangerous ambitions of foreign powers to exploit China and its resources.

During the 32nd year of the reign of the Guangxu Emperor (1907), Li Shi, an envoy of the Sichuan chapter of the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenghui) came to Jiangyou in order to organize local resistance fighters, establish a local chapter of the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, and eventually foment a local rebellion. Li Jie not only embraced the basic tenets of the Alliance, but became one of their most active and enthusiastic members. After a period of underground preparation work, it was decided that the time was ripe for launching a full-out rebellion and attack the local seat of the Qing government in Jiangyou County. During this raid, Li Jie was seen leading the charge with a sickle in his hands and cutting down the authoritative plaque at the gate of the Yamen, emblazoned with the words “The High Command of Mingjing.” This event caused a sensation in the entire region that sent a ripple effect through all of Sichuan. The head of government troops in Sichuan, General Xi Liang, immediately dispatched special units under Commander Zhang Xiaohou to quell the uprising. Since the rebels were few in number and had not undergone any martial training, the rebellion was quickly suppressed by a massive influx of troops and most of the resistance fighters perished in the ensuing blood bath. Since Li Jie was already a high level martial artist, he was able to defeat 4-5 Qing soldiers in hand to hand combat before breaking through the army’s tight encirclement and therefore was one of the few who got away with his life. Despite multiple searches at his house and a high prize offered for his capture, the government troops were never able to seize him. For a while he kept on the move, hiding himself in a variety of places.

Originally, he may have been eager to raise the flag of the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance once again and continue his calling as an anti-government rebel. But the organization had become deeply damaged by the army’s punitive counter-move and volunteers for new attacks by the rebels were now hard to find. Therefore, Li Jie decided to remain in hiding, and eventually took vows with an unknown monk with the common name Chen Linshan to become a Daoist adept on Sichuan’s Mt. Qingcheng. After this decision to become a disciple of the Dao, Li Jie experienced a complete change of lifestyle and spiritual environment. From now on, he left the affairs of the world alone and dedicated himself to the routine of burning incense, reading the classical texts, ring the temple bells and remove any trace of common indulgences from his everyday life. Nobody within the monastic world had any idea about his background, but it was understood that he must stem from special upbringing due to his high level of literacy and extraordinary ability to understand the Daodejing, the Taipingjing and other Daoist classics. In addition, Li Jie always completed every monastic task he was given and treated everybody with great kindness and respect. Therefore, after ½ a year in the monastery, Master Wang Zhenren gave him the formal epithet Huanxi Daoren (The Daoist With the Ubiquitous Smile). The monastery even conducted a naming ceremony to officially celebrate the event.

Huanxi (The Happy One) is indeed the best name to describe his character, since he was known to be always happy and full of laughter the moment he opened his mouth. No matter what situation he faced, he never appeared unhappy or depressed—as if any gloom and doom emotions were unfamiliar to him. Many people therefore believed that Li Jie was a happy man with an easy lot in life, somebody who had never seen battle or strife. We already know, however, that Li’s life was anything but easy, with a home and family destroyed and a life almost lost. He chose, however, to embrace an outlook of utmost positiveness and generosity instead. Due to his monastic practices and various forms of spiritual cultivation, this wild military warrior had in one instant transformed himself into a peaceful follower of the Dao.

At the same time, he was to save many of the people around him by applying the medical skills that he later became so refined at. In the secluded setting of the monastery, he applied himself to a rigorous regimen of studying all of the Daoist and medical classics that he could get his hands on, starting with the Daodejing and the Yijing, so that in a span of 3-4 years he obtained a wealth of information about Chinese medicine, herbs and Qigong. In order to improve both his cultivational and medical skills, he began to travel widely to sacred mountains such as Mt. Emei (Sichuan), Mt. Heming (Sichuan), Mt. Yunqi (Mt. Zhongnan; Shaanxi), and Mt. Qingxu (Mt. Wangwu; Henan). During these journeys, he studied with various masters, visited friends, and treated the local people along the way, always without charging a fee. During the 5th year of the Republic (1916), his travels brought him to Mt. Taihua in Jiange County (Sichuan) where he fell in love with the beauty of the local scenery. He ended up staying for more than 10 years.

In addition to his duties as a Daoist monk, he spent most of this time practicing the martial arts. He continued to treat the illnesses of the local populace, and was known for his ability to create ink drawings and recite poetry. He mastered the rare calligraphic styles of seal script and Daoist “cloud” script, and thus created a highly unique style. Specifically, he used to grow the nail on his little fingers very long, dip the long and sharp nail of his right little finger into ink, and draw on top of a special ink slab, painting mostly images of flowers, birds, insects and fish. After this kind of drawing was completed, he would cover the slab with a piece of paper, press lightly, and an ink drawing full of life-like birds and other creatures would appear like magic. This special type of ink slab drawing method was a unique creation of this multitalented Daoist master.

After becoming a monk, it had been Li Jie’s hope that he could leave the world with all of its woes behind and focus on his inner studies and cultivation in peace, but the brutal events of his time kept had a tendency to draw him back into the world. During the year 1935, the 4th regimen of the Red Army came to Mt. Taihua in Jiange and occupied the monastery. He couldn’t fail to notice that the army helped the causes of the poverty-stricken families of the region, and opposed the position of local government leaders, landowners and the nobility. He therefore began to help the cause of the Red Army by writing banners and engaging in other propaganda work. After one month, however, the Red Army left the region and was thrown back into their Long March northward. Immediately, the Republican Army entered the vacuum and tried to arrest Li Jie. He was faster than them, however, by walking several days and nights to reach the Buddhist Lingyin Monastery on Mt. Xiuzhong where he went into hiding once again.

In the rural environs of Lingying Monastery in Northern Sichuan, Li Jie continued to study the Han dynasty works attributed to the Yellow Emperor as well as the writings of the four great medical scholars of the Jin and Yuan dynasties. By now, he had become a master in the theory of yin and yang, the 5 phase elements, and the meridian system of Chinese medicine. His clinical specialty was the healing of external injuries. It is reported that one time a local woodcutter fell down a steep cliff and sustained splinter fractures to his entire body. Everybody involved thought that his situation was too severe for recovery, and that death was imminent. Li Jie, however, took it upon him to treat this person. He first used a set of uniquely Daoist medical techniques—opening the “gates”, closing wounds, decongesting meridians and then infusing the patient with his internal qi. Afterwards, he applied the traditional remedies Jiegu Dan (Reconnect the Bones Pellet) externally and Che’ao San (China Clam Powder) internally, and one month later the patient had not only survived the ordeal, but his extremities were still intact and his ability to move and work restored. This kind of amazing medical skill left every bystander with eyes bulging and jaws agape, believing that they were witnessing the workings of a true immortal master. In addition, Li Jie was also adept at treating all kinds of chronic and recalcitrant disorders, including gynecological problems. Besides using Chinese herbs and applying external poultices, he would use the shamanic Daoist healing technique of processing water with “fu” (magic symbols).

Every time when market fair day came around, he would appear—winter or summers rain or shine—with his paper, brush and ink, and a Taiji/Bagua map that he had used for this purpose for many years, and see people as patients or give them advice through the traditional procedure of interpreting a hexagram reading. He would help anyone who would come and ask for his advice. In this way, his name spread quickly around the county, and there wasn’t anybody who hadn’t heard about the miracle worker. During each fair, he would average several hundred patient contacts. In general, Lie Jie was a person who was not impressed by wealth and status, but made it his business to help the poor and the downtrodden. He always charged wealthy clients, while treatments for the poor and needy were always free of charge. It is reported that at the end of a market day he would take all of the paper money and silver pieces collected during the fair, put them into a cloth bag, and bring them back to the monastery where he would make it a habit to throw the bills at the statue of the Puxian Buddha. Later, once all money became dramatically devalued he would even use the bills to repair walls or make small paper dolls that he gave to children from surrounding farmer’s houses to play with.

In addition, Li Jie was an essential figure in the synthesis of a unique style of nourishing life practices that had its roots in the Yijinjing (Sinew Transforming Classic) tradition. This amalgamate of Daoist, Buddhist and Confucian practices was preserved and transmitted by a secret society composed of former military commanders, monks and hermits who had originally fled the secret police of the Manchu regime during the early 17th century for a reclusive life on sacred Mt. Emei in central Sichuan. During his studies in Daoist alchemy and the arts of internal cultivation, Lie Jie apparently studied under an unknown master in this tradition. Brothers on this cultivational path were Abbot Yang, a Daoist monk from Louguantai monastery in Shaanxi and the itinerant Daoist healer Xu “Aizi” (Xu the Dwarf), teacher of the late martial artist Wan Laisheng and founder of the well-known Ziranmen (Nature School) lineage of Qigong. During the 1940s, Li Jie coined his own version of this tradition under the name Jinjing Gong (The Sinew and Meridian Qigong Lineage).

Later in life, Master Li Jie often traveled to Chengdu and the surrounding countryside. His journey would invariably bring him to the Qingyang Gong monastery in Chengdu, as well as the Shangqing Gong and Yuqing Gong monasteries on Mt. Qingcheng. As before, he would continue his gongfu practice, and was particularly known for his unique sword form Yinba Bafang Jian (Yin Handle Eight Direction Sword), which in turn is remembered as consisting of two parts: Tieniu Jingdi (Iron Oxen Plows the Earth) and Gushu Pangen (Winding Roots of an Old Tree). In addition, he is remembered to have continued his practice of administering Yijing readings, entertain musings about the Dao and see the occasional patient. He is remembered as having led a quiet life of “carefree wandering” at a time when China was convulsed by the multiple spasms and purges following the formation of the Communist Republic in 1949. Reports about the time of his death diverge widely, varying between 1960 and 1983, postulating Li Jie’s age at the time of his death to be somewhere between 84-107. Like with so many Chinese esoteric masters of the tumultuous 20th century, the location of his grave is unknown.

From 1948-49, upon receiving a letter of recommendation from the great martial artist Du Xinwu, Li Jie trained the 11-year old Wang Qingyu in the art of Daoist medicine, including unique modalities of fingernail diagnostics, the technique of “opening the gates,” and the various forms and practices of the Jinjing Gong school. Wang Qingyu, Life-time Professor of Martial Arts and the Arts of Nourishing Life at the Sichuan Academy of Cultural History, survives today (2015) at the age of 78 as Li Jie’s only living disciple. His lectures on Jinjing Qigong and the unique practice of Daoist medicine can be accessed at the Associate Forum of ClassicalChineseMedicine.org. In addition, the various moving forms and quiet meditation practices of the Jinjing Qigong are an integral part of the curriculum for the Doctor of Science in Oriental Medicine degree of the College of Classical Chinese Medicine at National University of Natural Medicine (NCNM) in Portland, Oregon. At NCNM, Prof. Wang Qingyu’s disciples Heiner Fruehauf, William Frazier, Laura Regan, Tamara Staudt and Gregory Sax teach regular classes and weekend retreats on Jinjing Gong.

© 2015 Heiner Fruehauf

Hi Heiner,

I found this really interesting – and a little gem that this is one of the traditions of qigong we have at NCNM.

Quick question: what are your thoughts on the old legends of hermits, TCM docs, mystics, etc. greatly exceeding 100 years of age – like this guy: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Li_Ching-Yuen

Do you think these are just exaggerated stories of genuinely old people, or traditions where the father/son have the same name and thus it accounts for multiple generations? Or is there some element of truth?

– Alex

Alex,

Good question!

Chinese traditional culture definitely has been known to use exaggeration as a tool to transmit pertinent information, including the role of cultivation and Kidney essence in the achievement of longevity. On the other hand, I personally believe that as modern people we do not know much about the inner workings and the enormous potential of the gnostic life sciences anymore. It may be quite possible for human beings–aided by traditional practices that involve strict dietary measures and special longevity exercises–to age healthily beyond the seemly insurmountable threshold of 100 years.

According to Quan Van Nguyen’s account of his Oriental medicine training in 1960s Vietnam, “Fourth Uncle in the Mountain,” his extremely vital teacher already trained his father and grandfather, and must have been more than 100 years old at the time of his discipleship. Of living people who are approaching 100 and look and act like they are half a century younger is the very real 96 year old Turkish yoga master Kazim Gurbuz. Along with the first chapter of the Huangdi neijing (The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Medicine; the foundational text of classical Chinese medicine), yogi Kazim believes that everyone should be able to live 100-130 years as long as certain life style measures are strictly observed.

In the case of Li Qingyun, his emergence caused an extreme ruckus in 1920s China, and contemporary doubters like General Yang Sen initially did everything they could to disprove Li’s claims about his age. General Yang eventually came around to believing Li’s story, but his book “The Immortal: True Accounts of the 250 Year Old Man” (translated by Stuart Olson) are hardly convincing from the perspective of a critical modern reader. The main “proof” is a photograph that shows Li Qingyun with very long fingernails and a collection of Shanghai newspaper articles buzzing about the possibility that a man from the 1600s could still be alive.

So, my opinion about this issue can perhaps be summarized as follows: while most of the stories we hear about people who are hundreds of years old turn out to not be true, this fact does not necessarily mean that the human body-mind-spirit complex does not have the inherent potential to live and thrive way beyond the modern life expectancy of 75-85 years, especially when gnostic (and unfortunately neglected and forgotten) practices of “nourishing life” are employed.